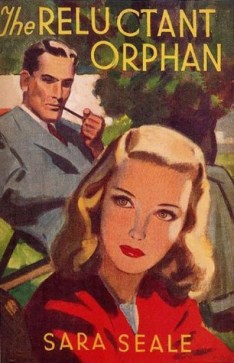

What I love about Sara Seale is the unashamed absurdity of her plots. Here, we have a man in his mid-thirties, who due to an injury, bitterness and heartbreak (if he has a heart – it’s never apparent) decides to go to an orphanage and pick out a girl to marry. He then chooses the least attractive and willing girl offered to him.

I don’t know how often this happened in the 1940s, but I’m betting not terribly frequently.

We’re in classic Sara Seale territory here. Julian Dane is tall, dark, glowering, handsome, in his mid thirties but frequently described as looking older.

Jennet is sixteen, as innocent as the morn, and right after Julian finally reveals his intentions to marry her – “in a year or so, when you’re older”:

…he put his hand under her chin, raising her face to his. “You are only a child, after all,” he said, and the first hint of tenderness she had known in him touched his mouth.

Jennet is instructed to call him “Cousin Julian” for half the book, then struggles to switch back to just “Julian”. I’m surprised Seale just didn’t go the whole hog and have him titled “Uncle Julian” (let’s not forget The Third Uncle).

Julian is controlling and overbearing throughout. He does all he can to “mould” Jennet to his requirements, continually lecturing her and and ordering various tutoring for her. Because of his leg injury, he refuses to allow her to learn to dance, swim or ride since he can’t engage in those activities. We’re repeatedly told that he chooses all Jennet’s clothes, which presumbly includes “her new silk underclothes”.

“I want to make you my sort of person. As you see, I’m somewhat restricted to the pursuits I can choose, so it’s better that we care for the same things.”

Even his friends accuse him of being “governessy” and an intellectual snob, and let’s not forget that this is a man whose previous romantic entanglement/engagement was with a shallow chorus girl.

The one, slim redeeming feature of this story is that Jennet does get a slight chance to experience other men and independence – Julian naturally freaks out each time. However, he never really gets his comeuppance and there is never any real sense that he feels sexually attracted to her, nor she to him. This is Mills & Boon and the 1940s, but Elinor Glyn and others were managing to get a bit of passion in by the early 1900s. Chaste is okay: this is frigid.

Jennet’s emotions towards Julian are a mix of gratitude, pity and subservience. Stockholm Syndrome might not have been defined by 1940, but this is it in spades.

Another theme that we frequently get in Sara Seale’s work is that of a young girl having to distance herself from “common people” – working class friends that she has to disassociate herself from as she grows up. I’m not sure why Seale makes such a point of this in so many of her novels. I’m struggling to think of a Seale novel I’ve read where there isn’t a “lower class childhood-friend/suitor” character.

One theme here that isn’t included, which is odd for a genre Romance such as Mills & Boon, is the Other Woman. There’s nearly always some glamorous, devious older woman who wants the hero for herself. Not here. It might have given Julian some humanity if we could have seen him react to such a character. Instead he’s a cold stick from start to end.

“I haven’t been lucky with women too date. They expect too much, and give too little.”

and:

She had to sit on her hands to prevent them from touching him, remembering that he disliked emotion.

and he even admits that he “never really liked women.”